Seon Ki Park and Kelvin K. Droegemeier

Center for Analysis and Prediction of

Storms and School of Meteorology

University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019

1. INTRODUCTION

Model parameters, both physical and computational, as well as initial and boundary conditions are essential factors in controlling the dynamical evolution of flows in atmospheric numerical models. For deep convective storms, their effects have been evaluated through the deterministic approach of sensitivity analysis (Park 1996), which employs a set of differential equations such as the tangent linear model (TLM) and the adjoint model (ADJM). Here, the sensitivity is defined as the gradient of the model response or output with respect to any input parameter.

Although having been used substantially for both sensitivity analysis and variational data assimilation in meteorology, the ADJM, especially of 3-D models, is still routinely generated by hand. The gradients can be computed efficiently and accurately by using automatic differentiation (AD) tools, which apply the chain rule systematically to elementary operations or functions to generate derivative codes of given nonlinear models. In this study, we apply a general purpose AD tool called ADIFOR (Automatic DIfferentiation of FORtran; Bischof et al. 1992) to the 3-D Advanced Regional Prediction System (ARPS; Xue et al. 1995) to generate a sensitivity-enhanced code (SE-ARPS) capable of providing derivatives of all model output variables and related diagnostic (derived) parameters (i.e., dependent variables; DV) as a function of specified control parameters, including initial and boundary conditions as well as physical and computational constants (i.e., independent variables; IV).

Given the strong influence that water vapor has on atmospheric processes,

particularly convective storms, we compute the sensitivity of model

outputs with respect to water vapor. We also compute sensitivities of the cost

function, which measures distance in the Euclidean norm between the observations

and model results, with respect to all model variables. Subsequently,

we discuss implications of the sensitivity results to data assimilation.

2. SENSITIVITY TO PERTURBATIONS

In 3-D models, the number of IVs is potentially very large when grid variables are considered, and this may inhibit the practical computation of sensitivity because of memory limitations. Although data assimilation requires the gradient of a cost function with respect to specified control parameters, we may need, in many forecasting problems, the sensitivities of model responses to perturbations only in specific regions. By introducing an artificial perturbation parameter, e, into ARPS, we let ADIFOR generate a sensitivity code that regards e as one of the IVs (Bischof et al. 1995).

For example, suppose the water vapor field, ![]() , is perturbed by a

factor e. Then any quantity P that is influenced by

, is perturbed by a

factor e. Then any quantity P that is influenced by ![]() implicitly depends upon e. Expanding P(e) in a Taylor series about the

reference state [P(e = 0)] and retaining only the first-order term, we

obtain an approximation to the sensitivity of P with respect to e:

implicitly depends upon e. Expanding P(e) in a Taylor series about the

reference state [P(e = 0)] and retaining only the first-order term, we

obtain an approximation to the sensitivity of P with respect to e:

![]()

Here, ![]() can be interpreted as the sensitivity of P to a uniform

fractional change in

can be interpreted as the sensitivity of P to a uniform

fractional change in ![]() . Accordingly, the relative sensitivity

coefficient (RSC) is defined as

. Accordingly, the relative sensitivity

coefficient (RSC) is defined as ![]() normalized by its nonlinear

counterparts (P/e) and

describes the percentage change in P due to a 1 % perturbation (e)

in

normalized by its nonlinear

counterparts (P/e) and

describes the percentage change in P due to a 1 % perturbation (e)

in ![]() (Park 1996).

(Park 1996).

Since the perturbation e is added to the input parameters, which

already have their own characteristic distribution in the

model domain, sensitivities

computed from this approach implicitly involve the characteristics of

those parameters. We limit our experiments only to ![]() at initial and

intermediate times excluding boundary conditions.

at initial and

intermediate times excluding boundary conditions.

3. MODEL, CONTROL SIMULATION AND TLM VALIDATION

We employ the full-physics ARPS (version 4.0), which is three dimensional,

fully compressible, and nonhydrostatic. The prognostic variables, solved on the

Arakawa C grid include Cartesian velocity components (u, v and w),

perturbations of potential temperature ( ![]() ) and pressure (p),

mixing ratios of water vapor (

) and pressure (p),

mixing ratios of water vapor ( ![]() ), cloud water (

), cloud water ( ![]() )

and rain water (

)

and rain water ( ![]() ), and turbulent kinetic energy.

An extensive description of the model can be

found in the ARPS user's guide (Xue et al. 1995).

), and turbulent kinetic energy.

An extensive description of the model can be

found in the ARPS user's guide (Xue et al. 1995).

The computational domain

consists of ![]() grids in the horizontal with a grid size of 1 km. In

the vertical, a stretched grid system is employed with 35 levels and a

resolution of 150 m near the ground and 850 m at the top.

The model is run for 140 min, with a large timestep of 6 sec and

a small timestep of 1 sec. The detailed model configuration for our

experiments is described in Park (1996).

grids in the horizontal with a grid size of 1 km. In

the vertical, a stretched grid system is employed with 35 levels and a

resolution of 150 m near the ground and 850 m at the top.

The model is run for 140 min, with a large timestep of 6 sec and

a small timestep of 1 sec. The detailed model configuration for our

experiments is described in Park (1996).

The simulation is made using the supercell HALF4 hodograph and thermodynamic

sounding from Droegemeier et al. (1993).

The simulated supercell develops rapidly during the first 30 minutes and

becomes quasi-steady thereafter, with a sustained updraft of around 47 m/s.

Major storm features including the surface outflow boundary (dotted lines)

are shown in Figure 1. The isolated supercell storm

becomes dominant after 60 min and travels southeastward along the

leading edge of the expanding cold pool.

A secondary storm develops northeast of the main storm after 100 min,

merging into the main storm by 140 min.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We investigate the effect of perturbations in ![]() within four different

regions of the environment: (

within four different

regions of the environment: ( ![]() ) inside the rain region above

cloud base, (

) inside the rain region above

cloud base, ( ![]() ) in the ambient environment outside the rain region

and above cloud base, (

) in the ambient environment outside the rain region

and above cloud base, ( ![]() ) the updraft region (including w = 0)

in the subcloud layer, and (

) the updraft region (including w = 0)

in the subcloud layer, and ( ![]() ) the downdraft region in the subcloud layer.

) the downdraft region in the subcloud layer.

We run the SE-ARPS starting

at 90 min, when the supercell storm is fully mature (see Figure 1b).

The cloud base at 90 min is around 485 m. Three model levels are involved

in the subcloud layer. The numbers of

grid points involved in perturbation are 8280 for ![]() , 61720 for

, 61720 for ![]() ,

5972 for

,

5972 for ![]() , and 4028 for

, and 4028 for ![]() .

Among the many available results, we discuss the sensitivity of

vertical velocity (w), which is

an important parameter describing storm intensity.

.

Among the many available results, we discuss the sensitivity of

vertical velocity (w), which is

an important parameter describing storm intensity.

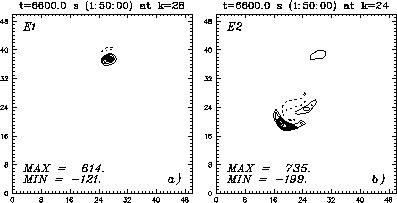

Figure 2 shows the domain maximum sensitivity of w at 110 min with respect

to perturbations ![]() and

and ![]() at 90 min.

At 110 min, in the control simulation, the main updraft is located near

the center of the domain with a lima-bean shape, while a prominent secondary

storm exists to the northeast. The sensitivities to

perturbations below cloud base (i.e.,

at 90 min.

At 110 min, in the control simulation, the main updraft is located near

the center of the domain with a lima-bean shape, while a prominent secondary

storm exists to the northeast. The sensitivities to

perturbations below cloud base (i.e., ![]() and

and ![]() ) are much smaller

than those above cloud base (i.e.,

) are much smaller

than those above cloud base (i.e., ![]() and

and ![]() ).

The location of the largest sensitivity differs for different

perturbations. The largest w sensitivity to the

).

The location of the largest sensitivity differs for different

perturbations. The largest w sensitivity to the ![]() perturbation occurs

in the secondary storm near the cloud top, while that to the

perturbation occurs

in the secondary storm near the cloud top, while that to the ![]() perturbation stays in the main storm at lower levels.

The maximum sensitivity value of 614 in Figure 2a implies a change of

w by 6.14 m s

perturbation stays in the main storm at lower levels.

The maximum sensitivity value of 614 in Figure 2a implies a change of

w by 6.14 m s ![]() due to a 1 % perturbation (

due to a 1 % perturbation ( ![]() ) in

) in ![]() .

For perturbations

.

For perturbations ![]() and

and ![]() , the largest sensitivity is observed at

both the main and secondary storms (not shown).

, the largest sensitivity is observed at

both the main and secondary storms (not shown).

|

|

Figure 2:

Domain maximum sensitivity of w at t = 110 min with respect to

the |

We now discuss the sensitivity results in the cost function and their

implications on data assimilation. The cost function, J, is defined as

the squared distance between the model states, ![]() , and the corresponding

observations,

, and the corresponding

observations, ![]() :

:

![]()

where ![]() denotes a scalar product between

denotes a scalar product between

![]() and

and ![]() and n represents the time index.

and n represents the time index.

![]() is a weighting factor matrix as defined in Park (1996). Applying this

factor, the cost function is nondimensionalized and normalized at the

beginning of the variational data assimilation window.

Sensitivities of J are computed for perturbations in all

model variables both inside and outside the rain region of the storm.

is a weighting factor matrix as defined in Park (1996). Applying this

factor, the cost function is nondimensionalized and normalized at the

beginning of the variational data assimilation window.

Sensitivities of J are computed for perturbations in all

model variables both inside and outside the rain region of the storm.

We consider the control simulation as our pseudo-observations. The sensitivity period is 30 min, from t = 80 min to t = 110 min. A 1 % perturbation is added to all variables at all grid points at 80 min for the perturbation run, which serves as the nonlinear basic field for the sensitivity computation. With this perturbation, model solutions show little difference from the pseudo-observations.

For perturbations inside the rain region, the largest sensitivity

in the cost function (i.e., forecasting error) is due to variablity in

![]() , followed by p and

, followed by p and ![]() .

Among the moisture variables inside the cloud,

.

Among the moisture variables inside the cloud, ![]() exerts the largest

influence on J, followed by

exerts the largest

influence on J, followed by ![]() and

and ![]() .

Perturbations in the momentum

variables (u, v and w) inside the rain region yield small changes in J.

The sensitivities are generally smaller for perturbations outside the rain

region. The largest sensitivity is due to

.

Perturbations in the momentum

variables (u, v and w) inside the rain region yield small changes in J.

The sensitivities are generally smaller for perturbations outside the rain

region. The largest sensitivity is due to ![]() ,

followed by

,

followed by ![]() and p.

Since

and p.

Since ![]() and

and ![]() are effectively

zero in the ambient air, the sensitivities of J to them are extremely

small.

are effectively

zero in the ambient air, the sensitivities of J to them are extremely

small.

Figure 3 depicts the RSC of J with respect to ![]() and p

inside the rain region. The p field has the largest effect on J

during the early sensitivity period. This is because p is directly

responsible for the mass balance through pressure gradient forces

in the momentum equations. When p is perturbed, the flow

accelerates until terms involving the velocity become comparable with

the pressure gradient force. Therefore, the flow immediately and

significantly responds to the p perturbations. In contrast,

perturbations in

and p

inside the rain region. The p field has the largest effect on J

during the early sensitivity period. This is because p is directly

responsible for the mass balance through pressure gradient forces

in the momentum equations. When p is perturbed, the flow

accelerates until terms involving the velocity become comparable with

the pressure gradient force. Therefore, the flow immediately and

significantly responds to the p perturbations. In contrast,

perturbations in ![]() affect the system initially through only the buoyancy

term in the vertical momentum equation, and then other variables through mass

continuity. Hence, during the early

sensitivity period, the p perturbations exert the largest influence on

forecast errors among all variables. However, the increased buoyancy

through the

affect the system initially through only the buoyancy

term in the vertical momentum equation, and then other variables through mass

continuity. Hence, during the early

sensitivity period, the p perturbations exert the largest influence on

forecast errors among all variables. However, the increased buoyancy

through the ![]() perturbation eventually influences storm dynamics and

forecast error.

perturbation eventually influences storm dynamics and

forecast error.

|

|

Figure 3:

Relative sensitivities of cost function with respect to

perturbations in |

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Center for Analysis

and Prediction of Storms under Grant ATM91-20009 from the National

Science Foundation (NSF) and by NSF Grant ATM92-22576 to the second author.

6. REFERENCES

Bischof, C., A. Carle, G. Corliss, A. Griewank, and P. Hovland, 1992: ADIFOR: Generating derivative codes from Fortran programs. Scientific Programming, 1, 11-29.

Bischof, C., G. Pusch, and R. Knoesel, 1995: Sensitivity analysis of the MM5 weather model using automatic differentiation. Preprint, MCS-P532-0895, Argonne National Laboratory, 14 pp.

Droegemeier, K.K., S.M. Lazarus, and R. Davies-Jones, 1993: The influence of helicity on numerically simulated convective storms. Mon. Wea. Rev., 121, 2005-2029.

Park, S.K., 1996: Sensitivity Analysis of Deep Convective Storms. Ph.D. thesis, School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, 245 pp.

Xue, M., K.K. Droegemeier, V. Wong, A. Shapiro, and K. Brewster, 1995: ARPS4.0 User's Guide. Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, University of Oklahoma, 380 pp.